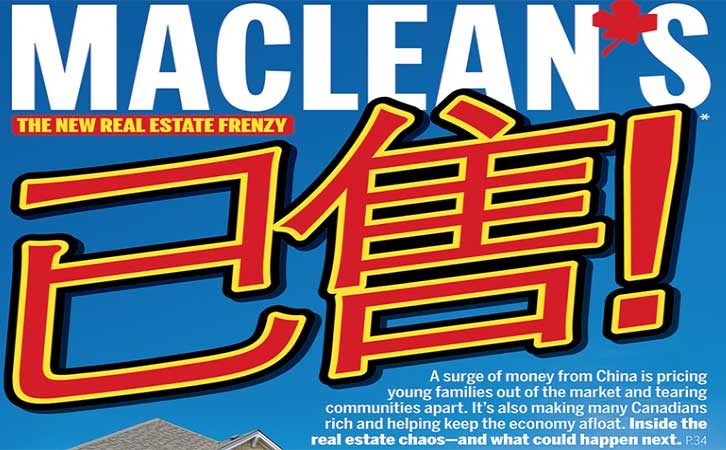

China is buying Canada: Inside the new real estate frenzy

- May 9, 2016

- Posted by: admin

- Categories: Investing, News

Paul Shen can tick off the reasons Mainland Chinese people buy property in Canada as surely as any fast-talking B.C. realtor. Some long to escape the fouled earth and soupy air of their country’s teeming cities, he explains, while others are following relatives to enclaves so well-populated by other Chinese expats they hardly feel like foreigners.

The richest, of course, regard homes in the West as stable vessels for disposable cash, but Shen lays no claim to such affluence. Last spring, the 39-year-old left behind his middle-management advertising job in Shanghai to seek the dream of home ownership he and his wife couldn’t afford in their home city. “We just followed our hearts to begin a totally different life,” he tells Maclean’s, adding: “We can make the house dream come true in Canada.”

The starting point was one-half of a modest duplex near downtown Victoria, close to the university where his wife is seeking a master’s degree, and priced about right for their limited means. Selling points ranged from the quiet of the street—perfect for their six-year-old son—to the stunning Vancouver Island vistas all around. High on his list, though, was Victoria’s comfortable distance from the bustling Chinese communities of B.C.’s Lower Mainland. As Shen—betraying his limited knowledge of pre-settlement Canadian history—puts it: “We wanted a place that would allow us to live with the natives.”

It’s hard not to smile at his idealism. Substitute any one of two dozen nationalities, after all, and you have a chapter in Canada’s cherished narrative of migration, settlement and shared prosperity.

But as a Chinese newcomer with a buy-at-all-costs resolve, Shen also personifies a phenomenon dividing those “natives” he’d like to call his neighbours. In the past five years, the flow of money from mainland China into Canadian real estate has reached what many consider dangerous levels, contributing to a gold-rush atmosphere in the nation’s leading cities, while stirring anger among young, middle-class Canadians who feel shut out of their hometown markets.

Its impact on Vancouver’s gravity-defying boom is the best known—and most hotly debated—example, as eye-popping price gains leave behind such quaint indicators as average household income, or regional economic activity. “We’re bringing in people who just want to park their money here,” says Justin Fung, a software engineer and second-generation Chinese-Canadian who counts himself among those frustrated by Vancouver’s surreal housing market. “They’re driving up housing prices and simply treat this city as a resort.”

Yet the amphetamine rush of Chinese cash has been felt far beyond the disappearing pastures of the Fraser Valley—especially in the last couple of years. Fully 10 per cent of new condominiums being built in central Toronto are now going to foreign buyers, according to a survey released in April by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC); veterans of the city’s rough-and-tumble real estate market believe the vast majority are mainland Chinese. On Juwai.com, an online listing service where Chinese buyers can look for international real estate, inquiries about specific properties in Ontario rose 143 per cent in 2015, with the total value of those homes hitting $11.2 billion. Quebec saw its numbers more than triple, while Alberta’s numbers rose 70 per cent.

Meanwhile, Chinese developers have made buys in locations that have left analysts scratching their heads, including Nova Scotia’s remote Eastern Shore and an abandoned mining town in the B.C. Interior. The stated reasons for such purchases don’t entirely compute (neither seems the likely site, as owners and local officials suggest, for a full-service, self-contained vacation community).

But the broader incentives are easy to see. Next to China’s own volatile real estate markets, property almost anywhere in the Western world can seem an island of financial sanity, says Matthew Moore, president of Juwai’s North American operations. “The year-on-year property increase in Shenzhen, one of China’s tier-one cities, was close to 60 per cent,” he observes. “This is about wealth preservation.” Adding to that sense of urgency: even the most privileged Chinese mainlanders have for decades been shut out of buying property, which Moore describes as the “favourite asset class” of Chinese dating back to its pre-Revolution days. This is on top of profound worries many Chinese have about their country’s overbearing political system, the lack of transparent rule of law and rampant corruption.

All of which has landed Canada in an economic paradox. In Vancouver, and increasingly Toronto, fear abounds that Chinese money has helped inflate a property balloon of Hindenburg proportions, driving house values out of reach for even well-off professionals, while raising the risk of a crash at the first sign of adverse conditions. Yet the self-same conditions are adding handsomely to the net worth of millions of homeowners, and supporting a constellation of housing-related industries, from real estate sales to interior decoration. They could be considered the main engine of Canada’s stop-and-go economy, and for those along for the ride—builders, property lawyers, revenue-hungry local politicians—the question isn’t so much what Chinese buyers are doing to the Canadian property market. It’s what might happen without them.

How far we’ve travelled down this bejewelled highway is only starting to come clear. The CMHC’s latest condo numbers tracking the ownership of condos were part of a concerted effort on the part of the Crown corporation to measure the phenomenon, based on its mandate to gather data on housing, and to foster market stability. (The agency has been roundly criticized in the past for Canada’s dearth of dependable real estate statistics.) By breaking down the numbers according to the age of the building in question, it provided the first reliable indicator of accelerated foreign buying. In Vancouver, for instance, foreign ownership of condos built before 1990 stands at just two per cent. For structures completed since 2010, that number climbs to six per cent.

CMHC’s plan now is to produce a more comprehensive report by the fourth quarter of this year, says chief economist Bob Dugan, capturing not just condominiums but all forms of residential property. But that won’t be easy. Gathering the data requires co-operation on the part of everyone from provincial property registries to local realtors—not all of whom are eager to shed light on their lucrative sources of new-found income.

It might also require a better understanding of who constitutes a “foreign owner.” The CMHC’s current definition—an owner who does not reside in Canada—excludes all kinds of domestic arrangements under which foreigners purchase homes abroad, suggesting the recent condo numbers understate the influx of outside buyers. It’s common for foreign-based buyers to send their children and spouses here while remaining in their home country. Should such buyers be lumped in with overseas owners of income properties? Or with Chinese Canadians who spend part of the year outside the country?

Yet even the crudest measurements suggest a breathtaking upsurge in interest that would rate Canada’s big cities on par with London and New York in the eyes of Chinese buyers. National Bank of Canada economist Peter Routledge has “hypothesized” that Chinese buyers last year shelled out nearly $12 billion on real estate in Vancouver, accounting for 33 per cent of the city’s sales. For Toronto, he pegged the number at $8.4 billion, representing 14 per cent of sales.

Other analysts have dismissed the estimate, which Routledge produced by combining U.S. foreign investment figures with a survey of property ownership among 77 affluent Chinese people. But the numbers seemed to support an earlier, more controversial, study of home sales in three of Vancouver’s most expensive neighbourhoods, showing that 66 per cent of houses sold during a six-month period starting in September 2014 went to Chinese people with non-anglicized names. The author of that report, an urban planning professor named Andy Yan, interpreted that to mean the buyers were new arrivals. That assumption was enough to draw accusations of racism, but Yan was undaunted, telling CBC, “It’s about the message, not one messenger.”

At least part of the message is beyond dispute: the cash flowing out of China into assets around the world has hit tsunami proportions, driven by fears of a slowing economy and a declining currency. Estimates peg the amount Chinese investors and companies moved out of the country last year at nearly $1 trillion, up more than sevenfold from 2014. Much of that money is being spent by Chinese companies looking to snap up Western assets, such as ChemChina’s US$43-billion bid to take over Swiss seed company Syngenta, or to pay down U.S. dollar-denominated debts. But a sizable portion was directed into overseas real estate.

With diversification as the new mantra, China’s newly rich—as of 2014 there were 3.6 million millionaires in the country—are desperately seeking safer places to park their money. Most put foreign real estate at the top of their list. That’s partly due to its stability, says Jim Zhang, an RBC private banker in Toronto, whose client list includes many so-called “high-net worth” Chinese investors; it’s also born of instinctive suspicion toward their own government. “In Canada, everything in my bank account is mine, as long as I pay tax,” a client recently told him. “In China, even if the government’s name is not on my account, whenever they want my money, they’ll have my money.”

Fortunately for those millionaires, a thriving industry has formed to facilitate their wishes to move their money abroad—and they need not even board a plane. In mid-April, more than 40,000 people crammed into the Beijing International Property & Investment Expo, a four-day mixer of buyers eager to snag deals and sellers eager to snag deep-pocketed investors. Representatives from 31 countries attended, but many of the land-shoppers veered toward the booths covered in Maple Leaf flags. The three Canadian exhibitors barely had time to sit.

Alex Majdpour, president of Sans Souci Executive Realty, hired two additional translators to keep up with the flood of potential buyers, and came away with 100 leads. “We thought, why not take the real estate to them?” says Majdpour, whose Toronto-based company sells properties across Canada. “Why not go straight to the source?” Prospective buyers talked to the Canadian exhibitors about making purchases in cash, and expressed the greatest interest in properties located around Vancouver and Toronto. The sellers fielded repeat questions about immigration and payments, particularly how to get money out of the country. (China limits foreign purchases of currency to $50,000 per year, and has been tightening controls to keep money from flowing elsewhere. This has left lingering questions about how so many mainland Chinese have been able to afford expensive houses abroad.)

There was another factor surely lurking in the minds of prospective buyers at the expo: Canada, with its weakened currency, is on sale. The yuan is fixed to the U.S. dollar, and as the loonie fell against the greenback over the last two years, it raised the buying power of Chinese real estate buyers. “If they’re thinking of buying property in Canada now,” says Zhang, the RBC banker, “they’re getting a 25 or 30 per cent discount.”

While experts try to determine how much money is flowing out of China, there’s no question a good deal of it has come to rest in leafy Vancouver neighbourhoods, sparking anxiety and deep divides in the community. So decoupled have local house prices become from economic fundamentals that it now requires a mind-boggling 109 per cent of the average household’s disposable income to service the costs—like mortgage payments and insurance—needed to own the average home in the city, according to research by the Royal Bank of Canada. There’s no sign things are about to slow down. A recent report by real estate firm Re/Max found prices surged by 24 per cent in the city during the first quarter compared to the same time last year, and pegged the average price of a single family home at $2 million. The real estate firm noted the emergence of a vicious cycle, as intense competition for houses caused would-be sellers to hold off on listing their homes (for fear they won’t be able to afford a new one) thereby limiting the available inventory and driving prices even further into the stratosphere.

The frenzy has taken a visible toll on one of the world’s “most livable cities,” resulting in hollowed-out neighbourhoods, absentee investors, and vacant, decrepit homes as huge numbers of investment properties simply sit unoccupied. What statisticians have been slow to chart has been ruefully documented in popular blogs like Vancouver Vanishes and Beautiful Empty Homes of Vancouver, which tracks empty, multi-million-dollar character and heritage houses.

Frustration has hit a boil, and it’s been on full display at a series of “emergency” housing town halls, headlined by the front bench of the Opposition NDP. Hundreds have turned out to sit in church basements to voice their concerns, and their anger. At one held last week at St. Paul’s Church in Vancouver’s Mount Pleasant neighbourhood, a new advocacy group with a darkly intimidating acronym HALT—Housing Action for Local Taxpayers—turned up with picket signs.

Among the day’s speakers was David Eby. The Vancouver MLA, a lawyer touted as a future NDP leader, is among those priced out of the local market. Eby and his wife, a nurse currently in medical school, recently sold their 530-sq.-ft., one-bedroom condo in Kitsilano, which was too cramped for the two of them and their 19-month-old toddler. “A two-bedroom condo in my constituency starts at $600,000—a non-starter for us,” he says. So they’re renting a $2,700-a-month two-bedroom condo at UBC. It is, to put it mildly, a sobering thought: the man many believe could one day lead B.C. might soon be priced out of the province’s foremost city.

Eby bristles at the Boomer notion this is all just a bunch of Millennial whining. “The expectation that young people have is not as advertised—it’s not a detached home they’re after. It’s: ‘Can I have a separate bedroom for my kids?’ If you spend 10 minutes talking to any of the Millennials who are just holding on in this city by their fingernails, you’ll realize very quickly these people are anything but entitled,” he says. “They’re living in substandard rental accommodation just for the privilege of being in Vancouver, and contributing to the economy here—and they won’t do that forever. They’re going to vote with their feet.”

Last November, the 38-year-old lawyer and former head of the B.C. Civil Liberties Association helped Andy Yan, acting director of SFU’s City Program, with his headline-grabbing study on home buying in Eby’s West Side riding. In addition to the incendiary data involving Chinese names, the study revealed that 36 per cent of owners on homes worth an average of $3.05 million listed their occupations as housewives or students with little or no income. Fully 18 per cent of the 172 homes purchased were not mortgaged by banks. That means on Vancouver’s West Side alone over a six-month period last year, roughly $100 million in cash came pouring into Canada, almost all of it from China. Yet the homeowners would in all likelihood pay little or no income tax. The total value of all homes sold in the study period topped a half-billion dollars.

Predictably, when Yan’s study was published, a chorus of voices, including former developer Bob Ransford, jumped to criticize Yan: “The danger is intolerance, racism, singling out certain groups of people saying they’re to blame for this,” said Ransford. But such labels have failed to muffle the debate, particularly as more and more Chinese-Canadian voices have begun calling out white developers and academics for making the claim. Fung, the software engineer, says he’s among those “deeply pissed off” by what he considers a slur: “The only people claiming racism are white Anglo-Saxon males—that’s it. These are the same guys trying to label Andy Yan—whose grandparents paid the head tax—a racist? It’s absurd.”

That sentiment is shared by Ian Young, the South China Morning Post’s Vancouver correspondent and author of the popular Hongcouver blog. Young, who is ethnically Chinese and was raised in Australia and Hong Kong, says the issue is one of money, not of race. “What defines those people in terms of their behaviour here in Vancouver, and in terms of their impact on affordability, is not their ‘Chineseness,’ it’s their ‘millionaireness,’ ” he says. “The idea that there is commonality to be found in the Chineseness—I find that kind of insulting. Why would you think that someone was better defined by the colour of their skin than the colour of their money?”

This is why Fung believes it is so vitally important for Chinese-Canadian voices to encourage a debate over the impact of foreign investment on the local market. “Chinese people have a tendency to be a little quiet, we tend to want to not create ripples—culturally it’s something we’re not comfortable with.”

One oft-cited culprit for the barrage of offshore money are government programs aimed at bringing wealthy foreigners to this country—namely Canada’s now-infamous Immigrant Investor Program. Created in 1986 by the Mulroney government, it granted permanent residency to any foreign citizen willing to fork over $800,000, repayable without interest after five years. In effect, Canada had a nearly two-decade run of selling passports—on the cheap. (The U.S. demanded its investor-class immigrants create at least 10 jobs each, and Australia charged twice what Canada did.)

In recent years, it became increasingly common for investor-class immigrants to set their children up in Canada to study, while the family’s main breadwinner continued to work and pay income taxes elsewhere. One federal study unearthed by Young showed that even after five years in Canada more than 60 per cent of investor-class immigrants reported no annual income earnings at all. And those who did reported earnings of just $21,000—less than that of refugees.

When the program was finally suspended in 2012, and subsequently cancelled altogether two years later, there was a backlog of some 65,000 applicants. Quebec, meanwhile, is still running its own, identical version. But very few of its investor-class immigrants actually remain in the province. Data collected by Vancouver lawyer Richard Kurland shows that 94 per cent of those who arrived in Quebec in 2008 left shortly thereafter—most bound for metro Vancouver.

David Duff, a professor at the University of British Columbia’s Peter A. Allard School of Law, calls such schemes “bizarre” since they do nothing to prevent wealthy newcomers from dodging Canadian income taxes, providing they spend less than 183 days per year in the country and maintain a residence and business overseas. “Others wonder why these folks get to be treated that way while the rest of us get taxed on our worldwide income,” says Duff, “And the consequence, as we’ve all seen, is the bidding up of house prices in Vancouver.” He’s seen it first-hand: Duff recently sold his own tony West Side home to an offshore buyer.

There’s another side to the story, however. Yuen Pau Woo, the former president of the Asia-Pacific Foundation of Canada, doesn’t dispute the impact of so-called “millionaire migrants” on Vancouver’s affordability crisis. But he takes issue with the notion Canada isn’t receiving anything in return. Eventually, Woo says, many wealthy Chinese who used the program to gain access to Canada seek to “align” their personal lives in Canada with their business interests overseas—if for no other reason than to minimize the stress of living apart from their families for six months of the year. As evidence, he points to the half-dozen Chinese firms, including Poly Culture Group, a division of a massive Chinese conglomerate, that he’s helped convince to set up shop in the Lower Mainland through a venture called HQ Vancouver. “Every single one has a Vancouver connection,” he says—usually a CEO or chairman who already owns a house in the city or sends his children to school there. “How many more of these kinds of opportunities are out there waiting for us to activate them?”

The silent, happy majority in all this, of course, is the thousands of Canadian homeowners who have sold their homes for an enormous profit, and the millions more watching their home values climb into the stratosphere—more than 70 per cent of Canadian households own their own home, and many are watching their property values soar with an eye to their retirement. In Richmond Hill, Ont., a Toronto suburb favoured by many Chinese investors, standard four-bedroom homes are now typically priced around $1.3 million, and routinely sell for $300,000 over asking. For now, this is a distinctly uptown economic problem.

With so much cash sloshing about, people outside Canada’s urban hot zones are understandably keen to join the merriment. Last spring, politicians and economic development officials in Nova Scotia welcomed with fanfare the purchase of a series of properties by DongDu International Group, a Shanghai-based development company touting plans for two full-service vacation resorts catering to wealthy, young Chinese professionals. It was hoped the developments would bring much-needed economic activity to the stagnant region of Guysborough County, northeast of Halifax. An additional pair of properties DongDu bought in the capital were supposed to be the beachhead for a centre of excellence for the film industry.

Draped in a souvenir tartan scarf, and accompanied by local dignitaries, the company’s founder, Li Hailin, traipsed through the grass in Guysborough last May for a groundbreaking. Since then, however, nary a shovel has touched the 1,300 hectares of land on the Eastern Shore, leaving many to wonder whether the development plans are for real. Michael Mosher, warden of the district of St. Mary’s, says his council has not yet seen a formal proposal, or a definite timeline. “Because of the state of the global economy,” he said, “they want to make sure when they launch the project, they’ve got the right timing.” A spokeswoman for the Halifax Partnership says the city’s economic development agency is no longer working directly with DongDu, noting that a memorandum of co-operation it signed with the firm expires next month. A request for an interview left with DongDu’s offices in Halifax went unanswered.

Still, even if Chinese investors are disproportionately focused on Toronto and Vancouver, there can be little doubt they’re playing a role in keeping the country’s decade-long housing boom from collapsing under its own weight. It’s difficult to overstate just how important real estate has been for the Canadian economy in recent years. A report a few years ago by Altus Group, a Toronto-based property consulting firm, estimated that home renovations alone contributed as much as four per cent of Canada’s GDP in 2014, or about $64 billion. Add in new home construction, realtors, lawyers and other associated industries and the residential housing industry is responsible for as much as 20 per cent of Canada’s economy. That’s to say nothing of the cottage industry in reality TV the country has spawned over the past decade—everything from Love It or List It and Property Brothers to the ubiquitous Mike Holmes.

With Canadians already owing $1.65 on average for every dollar of disposable income they earn, there were ready signs that domestic buyers were tapped out. The sudden influx of Chinese money over the past couple of years was akin to throwing gasoline onto a slowly dying fire. Which is why no politician in their right mind is likely to take a hard stance against foreign buyers. Says Duff, the UBC law professor, “Nobody wants to shut it down, because it’s like a drug. We always need another fix.”

The multi-trillion-dollar question for Canada’s vulnerable housing market, and the economy that increasingly depends on it, is whether China’s interest in buying Canada is a simply a passing fancy or a stabilizing long-term play. It’s one of the concerns the CMHC hopes to address by charting the behaviour of foreign buyers over time. “If investors are primarily in the market to make a quick buck—to buy a unit, make a capital gain over six months to a year, flip the unit and get out—that can be problematic behaviour,” says Dugan, the chief economist. “We would want to be able to measure to what extent that’s going on.”

Those who have studied the Chinese appetite for buying foreign properties sketch a less dramatic picture, albeit one that’s still less than reassuring. A survey of 150 agents in China by Investorist, an Australian company that markets international properties online, found the vast majority of would-be Chinese purchasers, nearly 90 per cent, have a budget between $500,000 and $1 million—not unlike many Canadians who are seeking to buy a home in Vancouver or Toronto these days. “The majority of Chinese buyers are families that can afford an investment property and possibly a second one,” says Jon Ellis, the company’s founder. “These are mom-and-pop investors who might own a car dealership or a bakery.” Moreover, the report found that most Chinese seeking to buy overseas “wish to use leverage where possible,” which may also have something to do with the need to circumvent Beijing’s $50,000-per-year limit on foreign transactions.

It all points to a group of foreign buyers that, while large and motivated, remain financially mortal, and can therefore be expected to panic alongside everyone else if Canada’s housing market begins to falter. And, as foreign money continues to flood both Toronto and Vancouver, there’s plenty of evidence of ultra-sketchy, speculative behavior that’s not limited to offshore buyers: bidding wars, properties purchased unseen and without conditions, so-called “shadow flipping” by realtors, the creation of shell corporations allowing buyers to avoid being named in transaction documents, accusations of money laundering, and unfair tax avoidance. The list goes on.

The risks for Canada don’t end there. While the turbulent Chinese economy has so far prompted China’s elite to move their money to locales perceived as safer, a full-blown crisis in the Middle Kingdom could well have the opposite effect. If offshore investors suddenly believe their livelihoods are at risk, they may have no choice but to quickly offload overseas houses and other assets in order to pay back creditors. In other words, instead of simply fretting about overzealous Canadians sparking a major housing crash, now we need to worry about a made-in-China crisis, too.

Can anything be done? In B.C., a group of economists is proposing a two per cent anti-speculation tax, which would penalize buyers who let homes sit empty. The idea is to generate a little revenue ($90 million is anticipated in the first year), but more important, to track activity: How many units are owned by people who don’t pay any tax in British Columbia? How many condo units are owned by people who don’t rent them out, and leave them vacant? How is this money entering Canada? At this point, the government doesn’t have a clue.

“If the flow starts in a clandestine way there is no way to regulate it at the other end,” says David Mulroney, former Canadian ambassador to China, adding that every time he spoke to university students in China he was asked whether it was true Canada is a haven for Chinese fraudsters. “We have no idea where the money is coming from, how it was sourced—all of it contributes to an alarming lack of awareness in the local real estate markets,” says Mulroney, current president of St. Michael’s College at the University of Toronto.

Others point to countries like Australia, which requires foreign purchases to be vetted by its foreign investment review board and approved only if they contribute to the creation of new housing stock. A similar approach has been proposed for the U.K. Ellis, however, says the policy hasn’t done much to rein in house prices Down Under, since there are many ways for determined offshore investors to circumvent the rules.

In any case, it’s not exactly Canada as the country imagines itself—cowering from foreigners willing to pay for a taste of our order and civility; wondering if the next big purchase will nudge us into social dislocation, or corruption requiring aggressive government intervention. If for no one else, you’d hope we might get ahead of the problem for the sake of Paul Shen, who’s settling into his new home in Victoria. Should such dark forebodings come to pass, the life he followed his heart to find will look eerily similar to the one he left behind.